Medicinal cannabis in the news for the wrong reasons

Friday, 18 July 2025

Despite generating hundreds of millions of dollars in sales and serving hundreds of thousands of consumers, Australia’s medicinal cannabis industry has its issues. This became part of the news cycle after July 9, when the Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency (AHPRA) issued a guidance reminding prescribers and dispensers of their responsibility to abide by AHPRA’s official Professional Guidelines.

These guidelines are not very different from other prescription drugs:

assessing patients thoroughly;

formulating and implementing a management plan;

facilitating coordination and continuity of care;

maintaining medical records;

recommending treatments only where there is an identified therapeutic need;

ensuring medicinal cannabis is never a first-line treatment; and

developing an exit strategy from the beginning.

What was newsworthy that it was necessary to remind the industry to follow these guidelines. Announcing that they’d deregistered 57 doctors, nurses and pharmacists, had another 60 under investigation, and were setting up a task force, AHPRA revealed widespread poor prescribing practices including:

very short consultations lasting few minutes at most, making a proper assessment impossible;

failing to fully assess patients’ medical history, coordinate care with patient’s other treating practitioners, or check real-time prescription monitoring (RTPM) to be aware of other medicines prescribed;

not checking patients’ identity, including prescribing for people under the age of 18;

prescribing just because the patient requested it and coaching patients to say “the right thing” to justify prescribing.

only prescribing the product supplied by a company the practitioner is associated with;

providing multiple prescriptions for a single patient so they can ‘try which one suits them’;

using "aggressive and sometimes misleading advertising that targets vulnerable people".

These issues have come up before. An investigation by the ABC 7.30 report in May uncovered similar poor prescribing practices. Academic research has also been published.

AHPRA accused many of the telehealth clinic/dispensaries of putting profits before patient wellbeing, and the evidence makes it difficult to argue with that. Though medicinal cannabis was only legalised in 2016, business is definitely booming. Between 2020 and 2024, prescriptions increased from around 17,000 to more than 800,000. However, this rise could’ve been affected by aggressive marketing and over-prescription, people accessing beneficial medication previously unavailable, and people who wanted cannabis for non-medicinal purposes but preferred getting it prescribed legally — though it’s hard to know how much influence each factor had.

Blurring the boundary between medicinal and non-medicinal use

A key issue identified is the one-stop telehealth model, with doctor and nurse prescribers solely prescribing cannabis products, which are dispensed online by dispensaries often owned by the same company as the prescribers. While their business model is problematic, and has caused harms, they are often chosen by people seeking cannabis medication due to stigma in the broader health system and many GPs not prescribing cannabis.

“The problem is that mainstream general practice practitioners are generally reluctant to prescribe medicinal cannabis,” Teresa Nicolleti, chair of the Australian Medicinal Cannabis Association, told SBS News. “There are now hundreds of thousands of scripts being issued, but they're being issued by telehealth clinics rather than GPs. There's only a very, very small proportion of GPs who will prescribe medicinal cannabis.”

The main issues with medicinal cannabis in Australia stem from a mix of factors — cannabis is a very popular drug and widely used, medicinal cannabis is legal, non-medicinal cannabis remains criminalised, and medicinal cannabis is produced and distributed by profit-focused commercial operators.

The current system financially incentivises the clinics and dispensaries to hard sell their products and blur the boundary between medicinal and non-medicinal use. Both markets are too profitable to ignore. A doctor who spoke to the 7.30 Report said she received pressure from a telehealth company not to deny patient’s prescription requests.

Both the lack of a thorough medical consultation and stronger products will attract more non-medicinal users as customers, though this can be dangerous for medicinal users. Because the medicinal use is what’s legal, this is generally what’s emphasised in the advertising.

Advertising

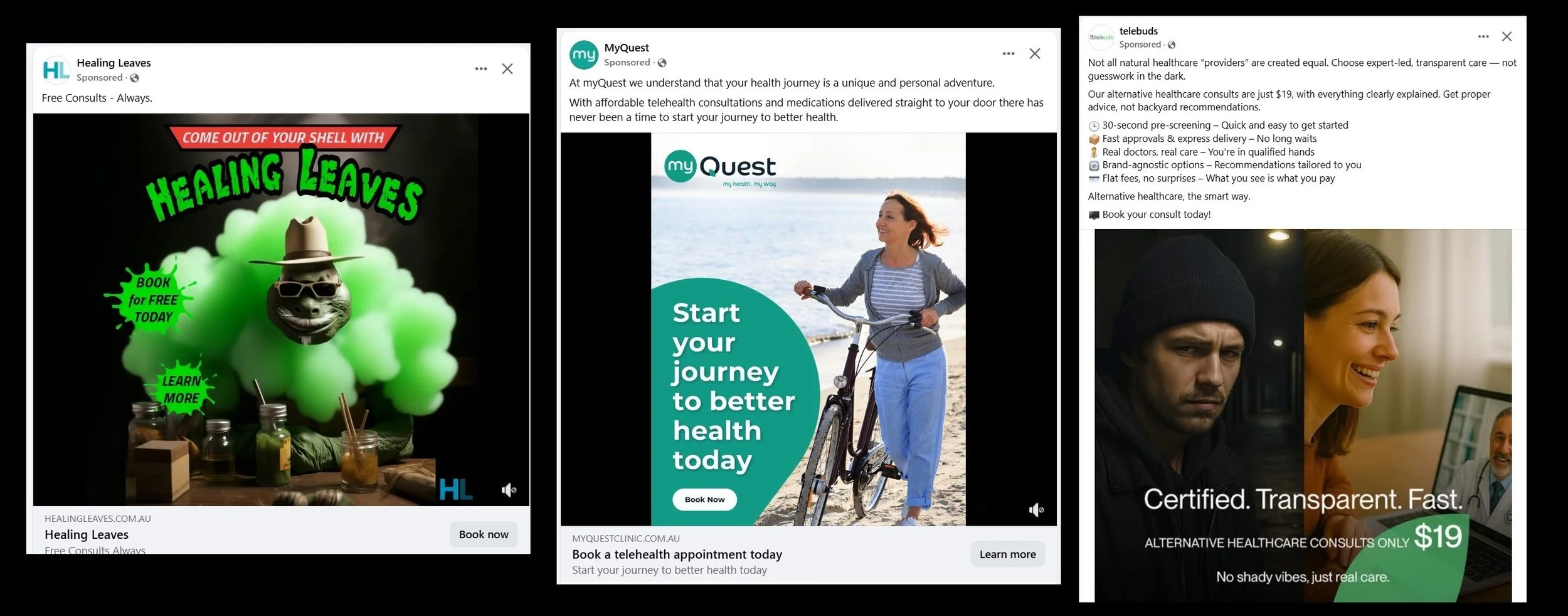

It is illegal to advertise prescription medicines in Australia. Despite this social media is full of advertisements for medicinal cannabis. They advertise clinics, not the product, but as the clinics only prescribe cannabis products, this is a technicality. Coded terms are used — “natural medicine” and “alternative plant-based medicine” are common. Some of the social media ads target non-medicinal users without much subtlety, with images like a ninja turtle emitting lots of green smoke.

The ads that use health and wellness imagery can be especially problematic—particularly when paired with 'consultations' that don’t assess a person’s medical history, drug use, or current health, and offer little information about the product itself. Most experienced cannabis users know that the effect from eating cannabis products lasts a lot longer than smoking or vaping. People with no experience of cannabis use should be told this before being given highly potent edible cannabis products.

Other advertising emphasises the safety of getting the product legally.

Cost

TGA-approved cannabis is not available on the Pharmaceutical Benefit Scheme (PBS). This makes it expensive and can be a barrier to access. Most cannabis obtained for medical use is still obtained on the illicit market. Medicinal cannabis should not be a privilege for those who can afford it, while people with less money must still risk criminalisation to access it. Prescribed cannabis having a higher price than illicit cannabis is another incentive for medical cannabis businesses to dispense strong weed, to attract non-medicinal users.

However, the government picking up the bill can further incentivise aggressive marketing. The Department of Veterans Affairs pays war veteran’s medical bills, including off-PBS medications. As a result, there are telehealth cannabis prescribers/dispensers that cater exclusively to veterans that advertise extensively on social media, targeting veteran’s support groups. A November 2024 ABC report featured several complaints from people who’d told the dispenser that they no longer wanted the medication, but it kept arriving. After all, the government was paying.

Legal weed for non-medical use

AHPRA’s crackdown has its merits. Prescribers who seek no information at all about their patients should be deregistered. Dispensers that badger clients who no longer want the product should be unlicensed. But with such lucrative financial incentives it's likely that poor prescribing practices will continue, even if a few providers are deregistered. Recriminalising medicinal weed is one solution proposed. The opposite is likely to be more effective. There were similar issues in Canada and several US states that legalised medical cannabis — legalising non-medicinal cannabis was adopted as a solution.

Legalising non-medicinal use would allow dispensers to simply sell pot, and market it as such. Legalised non-medicinal weed could be made safer by measures like requiring that the strength of products be tested and labelled, and easily available information about safer use and potential risks. It would also, if combined with educating GPs and other health professionals, allow medicinal users to get medication catered to their needs, rather than what sells best to non-medicinal users.

In Canada, in the 4 years following the legalisation of sale for recreation, medicinal sales dropped by 29%, the number of people registered to be prescribed it dropped by 32%, and there were changes in which medicinal products were the most popular.

There are a number of different models for legalising non-medicinal use. The US states that allow it, predictably, have an entirely commercial model. In some Canadian provinces it is only available in government-run shops. Canada has a history of regulating alcohol and tobacco this same way.

In some other countries, for example, Uruguay, Malta and Spain, legal distribution is through non-commercial “cannabis clubs”.

Solutions

Whatever legalisation model Australia adopts, if it takes non-medicinal users out of the medicinal cannabis market it will remove the incentives for many of the practices identified by AHPRA. Putting medicinal cannabis on the PBS — making it available to everyone, rather than just those that can afford it — will mean fewer people relying on illicit markets for medical needs. Reforms like these would not get rid of the need for bodies like AHPRA to enforce regulations, but it would make their workload a lot lighter.